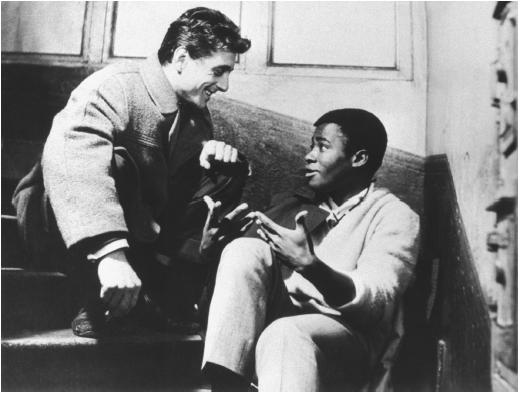

Jean Rouch & Edgar Morin - Chronicle of a Summer

Chronicle of a Summer is a film about a summer in Paris and in St. Tropez in 1960. The film follows the lives of several characters and try to tell their stories. All characters have some kind of special aspect; a jewish gilr who survived the holocaust, an immigrant Italian girl, a French labaourer and a black immigrant from French Africa all have fascinating stories about their life expereiences in France and Paris.

Rouch in his films wants to sinthesyze the ideas of Robert Flaherty and Dziga Vertov and hence create a bridge between cinéma-vérité and cinéma-direct. Therefore Chronicle of a Summer is a film that tries to bring in the personal reflexivity of the characters and build on their subjectivities in order to get a sense of the reality of their lives. Hence, the film moves along the fine line between fiction and ethnography that Steven Feld calls 'filmic ethnographic fiction'. From this definition too it is perfectly clear that Rouch is very preoccupied with the problems of subjectivity and reflexivity. In the beginning of the film he and Morin discusses whether it is possible to act natural in front of the camera or not. Thus the film can be considered as an experiment in making a movie about real life by focusing on people reflecting upon themselves and discussing their subjectivities.

Chronicle of a Summer is very different to other ethnographic or sociological films in a sense that Rouch and Morin kind of guide the characters, who are not actors, by giving them current topics that were very prevalent in France in the 60s, and after filming them discussing those topics they make them reflect on their own performances up until that time. As Feld states the film: "...combines the techniques of drama, fiction, provocation, and self-conscious reflexivity and critique that Rouch developed from previous films. In my opinion Rouch managed to create a film that doesn't want to pretend to be completely objective but still present the realities of its characters and the social problems of that time perfectly. I got a very clear feeling about the life in Paris during the 60s and about the sociological and international problems that interested people back then. The ideas of exploitation of the labouring classes, the brutal past that had to be yet faced and the slow collapse of the French colonal empire topped with huge waves of immigrants from ex-colonies in Africa are all incorporated into the film. This gives a great insight into the life back then and into the lives of the characters.

The film is full with constructed scenes, like the scene where the girl who survived the Holocaust walks slowly in Paris telling her and her family's story before and after the 2nd World War, reflecting on her own feelings about the historical events. Based on these parts of the film one could argue that it's not an ethnographic piece of work, I would argue with that. I think this film gives a full and real picture of French society during tat time.

The other very interesting aspect of the movie is the end where Rouch and Morin make the characters reflect upon their performance as if they were actors and actresses. It was very interesting to see what they thought of themselves and each other. They criticise each other when they felt that instead of being truthful one of them was being overly dramatic or played a fake role in certain scenes.

I, for one, felt that the film and the characters were very truthful and showed an objective picture of France in many ways. The participation of the film makers in the film and the discussion about whether someone can act naturally in front of the camera brought the characters even closer to me and their stories became more real.

2011. április 14., csütörtök

Gandhi's Children

MacDougall - Gandhi's Children

Gandhi's Children is probably the most famous film of David MacDougall. The movie takes place in an shelter for homeless children in India and shows the hardships of the lives of children living there and their parents.

The film shows MacDugall's approach, that he describes in his writings in Visual Anthropology and the Ways of Knowing, to ethnographic cinema very well. MacDougall is one of the biggest advocates of developing a visual language for anthropology so anthropologist would use modern techniques like photography and cinematography for their own value not just to record data. However he also warns social scientists not to use visual as a substitute for the verbal but to complement it. He developed his own way of filming different social problems within diffrent cultures that is very human and shows an initmate understanding of the cultural context in which these problems exist.

MAcDougall argues for transcultural cinema in ethnographic film making. For him, and that's clear from this film too, it's not enough to go somewhere and film different cultures but think about our western audience the whole time. It's also not enough to just show the audience a different culture without any kind of explanation or relatioship with the subjects of the film. Therefore the biggest difference between Gardner's Forest of Bliss and Gandhi's Children is that the local language is subtitled and the people being filmed have interactions with the camera several times. MacDougall doesn't try to force a false objecticity onto his films, he tries to be self-reflexive, which means that he has just as much contact with the subject of his films as with his audience. As he puts it: "If I am self-reflexive, that self-reflexivity must be about the relationship between us [him and the subjects], not a way of speaking behind my hand to some foreign audience."

From this quote too it is prefectly clear that for MacDougall it is not enough to just go somewhere and film 'objectively' what one sees. An ethnographic film maker should build an intimate,self-reflexive and interpretative relationship with his subject so he can show his audience the reality of the things he had filmed.

This approach is very clear in Gandhi's children. The audience can easily follow the events in the film because of the subtitles, they can get a sense of being there through the intimate cultural knowledge of MacDougall who had selected events and scenes from the kids' lives that are pivotal in understanding the culture in India. Also, the people on the film interact with the camera several times, explaining MacDougal what they are doing and why they are doing it. Surprisingly, this doesn't really bring a level of subjectivity to the film that'd be annoying, rather it brings a different type of objectivity than the one in Forest of Bliss; and in my opinion MacDougall's approach brings India's culture to his audiences a lot closer and in a much more digestable way.

Gandhi's Children is probably the most famous film of David MacDougall. The movie takes place in an shelter for homeless children in India and shows the hardships of the lives of children living there and their parents.

MAcDougall argues for transcultural cinema in ethnographic film making. For him, and that's clear from this film too, it's not enough to go somewhere and film different cultures but think about our western audience the whole time. It's also not enough to just show the audience a different culture without any kind of explanation or relatioship with the subjects of the film. Therefore the biggest difference between Gardner's Forest of Bliss and Gandhi's Children is that the local language is subtitled and the people being filmed have interactions with the camera several times. MacDougall doesn't try to force a false objecticity onto his films, he tries to be self-reflexive, which means that he has just as much contact with the subject of his films as with his audience. As he puts it: "If I am self-reflexive, that self-reflexivity must be about the relationship between us [him and the subjects], not a way of speaking behind my hand to some foreign audience."

From this quote too it is prefectly clear that for MacDougall it is not enough to just go somewhere and film 'objectively' what one sees. An ethnographic film maker should build an intimate,self-reflexive and interpretative relationship with his subject so he can show his audience the reality of the things he had filmed.

This approach is very clear in Gandhi's children. The audience can easily follow the events in the film because of the subtitles, they can get a sense of being there through the intimate cultural knowledge of MacDougall who had selected events and scenes from the kids' lives that are pivotal in understanding the culture in India. Also, the people on the film interact with the camera several times, explaining MacDougal what they are doing and why they are doing it. Surprisingly, this doesn't really bring a level of subjectivity to the film that'd be annoying, rather it brings a different type of objectivity than the one in Forest of Bliss; and in my opinion MacDougall's approach brings India's culture to his audiences a lot closer and in a much more digestable way.

Salesmen, Titicut Follies and Forest of Bliss

This week it was time for us to submerge into so-called observational cinema through three different films. First was the Salesmen by the Maysles brothers, the second was Titicut Follies by Wiseman and the last one was Forest of Bliss by Gardner.

Salesmen is about Bible salesmen who go all over America to sell special editions of the Bible. This film is one of the prototypes of American observational cinema. The camera and the film makers are basically invisible and they try to observe and film the subjects natural behaviour. As Anna Grimshaw says in her article 'Rethinking Observational Cinema' this was a revolution in ethnographic film making that tried to make visual anthropology more scientific by not creating a narrative and letting things just happen in front of the lense of the camera. As she puts it, observational cinema is "...a form of scientism in which a detached camera served to objectify and dehumanise the human subjects of its gaze."

This aesthetic definition clearly clearly fits Salesmen and Forest of Bliss but not Titicut Follies. Titicut Follies was shot in an asylum for the criminally insane in the state of New York and it tries to explore the fine line between normality and insanity. Wiseman's film has elements that fit observational cinema perfectly still it has a very clear message and agenda to criticise psychiatry and institutionalisation of people. Through these aspects Titicut Follies fits the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s, 1970s too. Many social scientists and psychiatrists, led by Thomas Szasz

questioned the methods and the validity of psychiatry and the existence of mental illness during these decades, and Wiseman does the same thing in this film. He uses methods that make his film look like observational cinema but the editing and the narrative that is sewn into the film send a clear message. He questions the normality of the staff of the asylum and contrasts it with the insanity of the patients or inmates. His portrayal of the place, the interaction between people and the brutality of several methods make the audience question the normality of the personnel. Wiseman tries to show that mental illness is socially created many times and that normality is highly subjective.

We don't really see any of that in Gardner's Forest of Bliss which was the worst movie experience I've ever had. It wasn't my worst experience because it is bad bad film necessarily, but the way it was done was so in-your-face that I felt like my senses got attacked. I felt violated by the things I was being shown and the sounds that were very overdone on purpose.

Forest of Bliss shows the life of an Indian city without any kind of explanation about the events and things that are happening in front of our eyes. We have some main characters like the slightly crazy healer or the very antipathetic guy who ran the place where people took their dead to get chremated, and the film has a loose narrative that follows the events that lead up to people's funerals. Although many people argued in class that the film was about life and death, light and dark, I didn't really see that. I got the feeling from the film that life in India is all about death and nothing else.

Which wouldn't have been a problem, on the contrary, I liked the film up until around the 50th minute, by tha time it was perfectly clear what the film was about, I got the whole picture in my head and I just wanted it to stop; the scenery, the sounds, the events; everything. By the end of the first hour of the film I thought: I get your point, just leave me alone.

I think for me that fact that nothing was explained made the whole thing worse. I was shown horrible poverty, squalor, death and they were all presented in a very emotionless and brutally stripped way without any kind of explanatory tools. Because of this I hated the film but I can say that it very well fits the criteria of observational cinema that has been very widely criticised.

I've already mentioned Grimshaw's article, but I haven't mentioned her critique of observational cinema. In her, and other's, opinion pure observation that records natural behaviour is impossible.

The subjects will always be conscious about being filmed and therefore the bedrock of observational cinema is fundamentally flawed. That's why many argue for a different aesthetic approach to ethnographic film making where the makers acknowledge the fact that they are in some kind of interaction with their subjects. Some kind of interpretation aproach or a more reflexive, self-conscious approach to visual anthropology that is advocated by MacDougall or Nichols.

Salesmen is about Bible salesmen who go all over America to sell special editions of the Bible. This film is one of the prototypes of American observational cinema. The camera and the film makers are basically invisible and they try to observe and film the subjects natural behaviour. As Anna Grimshaw says in her article 'Rethinking Observational Cinema' this was a revolution in ethnographic film making that tried to make visual anthropology more scientific by not creating a narrative and letting things just happen in front of the lense of the camera. As she puts it, observational cinema is "...a form of scientism in which a detached camera served to objectify and dehumanise the human subjects of its gaze."

This aesthetic definition clearly clearly fits Salesmen and Forest of Bliss but not Titicut Follies. Titicut Follies was shot in an asylum for the criminally insane in the state of New York and it tries to explore the fine line between normality and insanity. Wiseman's film has elements that fit observational cinema perfectly still it has a very clear message and agenda to criticise psychiatry and institutionalisation of people. Through these aspects Titicut Follies fits the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s, 1970s too. Many social scientists and psychiatrists, led by Thomas Szasz

questioned the methods and the validity of psychiatry and the existence of mental illness during these decades, and Wiseman does the same thing in this film. He uses methods that make his film look like observational cinema but the editing and the narrative that is sewn into the film send a clear message. He questions the normality of the staff of the asylum and contrasts it with the insanity of the patients or inmates. His portrayal of the place, the interaction between people and the brutality of several methods make the audience question the normality of the personnel. Wiseman tries to show that mental illness is socially created many times and that normality is highly subjective.

We don't really see any of that in Gardner's Forest of Bliss which was the worst movie experience I've ever had. It wasn't my worst experience because it is bad bad film necessarily, but the way it was done was so in-your-face that I felt like my senses got attacked. I felt violated by the things I was being shown and the sounds that were very overdone on purpose.

Forest of Bliss shows the life of an Indian city without any kind of explanation about the events and things that are happening in front of our eyes. We have some main characters like the slightly crazy healer or the very antipathetic guy who ran the place where people took their dead to get chremated, and the film has a loose narrative that follows the events that lead up to people's funerals. Although many people argued in class that the film was about life and death, light and dark, I didn't really see that. I got the feeling from the film that life in India is all about death and nothing else.

Which wouldn't have been a problem, on the contrary, I liked the film up until around the 50th minute, by tha time it was perfectly clear what the film was about, I got the whole picture in my head and I just wanted it to stop; the scenery, the sounds, the events; everything. By the end of the first hour of the film I thought: I get your point, just leave me alone.

I think for me that fact that nothing was explained made the whole thing worse. I was shown horrible poverty, squalor, death and they were all presented in a very emotionless and brutally stripped way without any kind of explanatory tools. Because of this I hated the film but I can say that it very well fits the criteria of observational cinema that has been very widely criticised.

I've already mentioned Grimshaw's article, but I haven't mentioned her critique of observational cinema. In her, and other's, opinion pure observation that records natural behaviour is impossible.

The subjects will always be conscious about being filmed and therefore the bedrock of observational cinema is fundamentally flawed. That's why many argue for a different aesthetic approach to ethnographic film making where the makers acknowledge the fact that they are in some kind of interaction with their subjects. Some kind of interpretation aproach or a more reflexive, self-conscious approach to visual anthropology that is advocated by MacDougall or Nichols.

Vertov Meets The Cinematic Orchestra to Lead in Hukkle and Angel Makers

Dziga Vertov: man with a Movie Camera

First of all I have to say that I loved Vertov's film, Man with a Movie Camera and the soundtrack done by The Cinematic Orchestra. I felt that the film was amazingly modern considering how old it is and the equipment that was used to make it. In my opinion Vertov manage to represent his famous kino eye and show the world that there is an option to shoot films differently.

In the film the camera plays the main role and Vertov turns this machine into a living being that's pivotal in order to show people things that are completely invisible for the naked eye. The camera takes us everywhere, from the city to the mines, from the beach to the factory and from the sea to the top of bridges. Vertov's mission to put machines into the nucleus of film making is beautifully accomplished in this film. And still there is something amazingly human and uplifting about this peace of art. We are invited to a journey into people's lives and we can watch a city sleeping silently and then filling up with life slowly as the day starts. We are invited to watch and observe every aspect of the human experience from birth to death, from work to playing games and from marriage to divorce. Furthermore, all during these things Vertov using techniques that give a fantastically modern feel to the whole film.

Vertov also incorporated the making of the film into the whole movie. We are taken to the editing desk and then we are dragged into the celluloid to see what's on it. A fantastic journey between the story and the making of the story. Even though, as I have mentioned, Vertov's goal was to put the camera into the central role, I think that maybe unintendedly he created a hero out of the cameraman too. I felt this way especially in the scenes when the cameraman is walking with the camera on his shoulder and the crowd opens up for them, or when he climbs high places to shoot things from up above.

There's also a propagandistic aspect to the movie even though it's not őrevalent enough to become annoying. The life that it shows is mostly full with happy people enjoying life, work and pastime. Sadness hardly ever shows up in the film and the whole movie is filled with some kind of joyous gloriousness that sweeps away any kind of bad feelings. A portrayal of the early years of the communist Soviet Union that is very misleading in retrospect.

All in all, Vertov reaches his goal with this great film. He emphasises the heroic aspects of the camera and the ways we can see the world better through the lense than through our own eyes. The kino eye prevails.

Hukkle & Angelmakers

It was very interesting to see a film and a documentary about the same events that happened in Hungary between the two world wars. Hukkle and Angelmakers both explore the murders committed by housewives who killed more than 200 men. Hukkle works with fairly regular techniques to show the events whilst Angelmakers uses a documentaristic approach. Hukkle is played mostly by locals but professional actors play in it too, on the other hand Angelmakers works with interviews with locals, narration and historical facts in the end.

So we have two completely different films with two completely different approaches to the same story. I found it weird and funny but I felt that Hukkle was more true to the feeling of the whole story even though we didn't find out the exact facts while watching it. We didn't find out how many men were killed, who were the killers, who was the ring leader or what was the aftermath of the events. Still I felt that the melancholic undertone of the film and the way the camera always moved through things to get behind the events or places while we were watching them brought a sense of mistery but also truthfulness and sadness to the film. Since there are no written scripts in Hukkle that actors would recite, the whole story is told through pictures and those pictures are amazingly beautiful. The story slowly unfolds in front of our eyes to the rythm of a hiccup and it takes time for the audience to realise what's going on; but when you realise it the whole film becomes very sad, tense, misterious and exciting. Hukkle also gives a great insight into the village's life and into the grievances that followed the deaths. Hukkle doesn't want to judge or to have a moral, it just shows a gtrotesque artistic picture of the events that mirrors some kind of objectivity.

On the other hand Angelmaker is supposed to be a completely objective documentary about the husband killings. The makers go to one of the villages where the murders happened and interview people and tell the historic facts. Still I felt that even though all the aspects of a documentary were implemented in the film, it was quite subjective. The film shows a fairly positive picture of the women who killed their husbands and tries to spur some sympathy in the audience towards the killers by arguing that most of them were drunk, aggressive bastards who beat their wives on a regular basis. I'm not saying that these things are not true and that one cannot feel even a crumble of sympathy towards those women, but the almost complete lack of voices in the movie that would condemn their actions is quite weird from a film that shows itself as a documentary and uses all the filming and story-telling techniques of documentary films.

In sum, for me the biggest epiphany, seeing these two films, was the fact that a visual presentation of events can be very objective and true even if it is presented artistically, and that it can be very subjective and packed with hidden agendas even if it is presented in a documentaristic way.

First of all I have to say that I loved Vertov's film, Man with a Movie Camera and the soundtrack done by The Cinematic Orchestra. I felt that the film was amazingly modern considering how old it is and the equipment that was used to make it. In my opinion Vertov manage to represent his famous kino eye and show the world that there is an option to shoot films differently.

In the film the camera plays the main role and Vertov turns this machine into a living being that's pivotal in order to show people things that are completely invisible for the naked eye. The camera takes us everywhere, from the city to the mines, from the beach to the factory and from the sea to the top of bridges. Vertov's mission to put machines into the nucleus of film making is beautifully accomplished in this film. And still there is something amazingly human and uplifting about this peace of art. We are invited to a journey into people's lives and we can watch a city sleeping silently and then filling up with life slowly as the day starts. We are invited to watch and observe every aspect of the human experience from birth to death, from work to playing games and from marriage to divorce. Furthermore, all during these things Vertov using techniques that give a fantastically modern feel to the whole film.

Vertov also incorporated the making of the film into the whole movie. We are taken to the editing desk and then we are dragged into the celluloid to see what's on it. A fantastic journey between the story and the making of the story. Even though, as I have mentioned, Vertov's goal was to put the camera into the central role, I think that maybe unintendedly he created a hero out of the cameraman too. I felt this way especially in the scenes when the cameraman is walking with the camera on his shoulder and the crowd opens up for them, or when he climbs high places to shoot things from up above.

There's also a propagandistic aspect to the movie even though it's not őrevalent enough to become annoying. The life that it shows is mostly full with happy people enjoying life, work and pastime. Sadness hardly ever shows up in the film and the whole movie is filled with some kind of joyous gloriousness that sweeps away any kind of bad feelings. A portrayal of the early years of the communist Soviet Union that is very misleading in retrospect.

All in all, Vertov reaches his goal with this great film. He emphasises the heroic aspects of the camera and the ways we can see the world better through the lense than through our own eyes. The kino eye prevails.

Hukkle & Angelmakers

It was very interesting to see a film and a documentary about the same events that happened in Hungary between the two world wars. Hukkle and Angelmakers both explore the murders committed by housewives who killed more than 200 men. Hukkle works with fairly regular techniques to show the events whilst Angelmakers uses a documentaristic approach. Hukkle is played mostly by locals but professional actors play in it too, on the other hand Angelmakers works with interviews with locals, narration and historical facts in the end.

So we have two completely different films with two completely different approaches to the same story. I found it weird and funny but I felt that Hukkle was more true to the feeling of the whole story even though we didn't find out the exact facts while watching it. We didn't find out how many men were killed, who were the killers, who was the ring leader or what was the aftermath of the events. Still I felt that the melancholic undertone of the film and the way the camera always moved through things to get behind the events or places while we were watching them brought a sense of mistery but also truthfulness and sadness to the film. Since there are no written scripts in Hukkle that actors would recite, the whole story is told through pictures and those pictures are amazingly beautiful. The story slowly unfolds in front of our eyes to the rythm of a hiccup and it takes time for the audience to realise what's going on; but when you realise it the whole film becomes very sad, tense, misterious and exciting. Hukkle also gives a great insight into the village's life and into the grievances that followed the deaths. Hukkle doesn't want to judge or to have a moral, it just shows a gtrotesque artistic picture of the events that mirrors some kind of objectivity.

On the other hand Angelmaker is supposed to be a completely objective documentary about the husband killings. The makers go to one of the villages where the murders happened and interview people and tell the historic facts. Still I felt that even though all the aspects of a documentary were implemented in the film, it was quite subjective. The film shows a fairly positive picture of the women who killed their husbands and tries to spur some sympathy in the audience towards the killers by arguing that most of them were drunk, aggressive bastards who beat their wives on a regular basis. I'm not saying that these things are not true and that one cannot feel even a crumble of sympathy towards those women, but the almost complete lack of voices in the movie that would condemn their actions is quite weird from a film that shows itself as a documentary and uses all the filming and story-telling techniques of documentary films.

In sum, for me the biggest epiphany, seeing these two films, was the fact that a visual presentation of events can be very objective and true even if it is presented artistically, and that it can be very subjective and packed with hidden agendas even if it is presented in a documentaristic way.

Feliratkozás:

Bejegyzések (Atom)